Key Takeaways:

- A new study proposes that Mercury's anomalously large core-to-mantle ratio, a long-standing mystery, can be explained by a grazing "hit-and-run" impact between two similarly sized protoplanets, rather than a single catastrophic collision.

- Utilizing Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) simulations, researchers demonstrated that a low-velocity, grazing impact between two proto-planets of comparable mass could strip up to 60% of the mantle, accurately reproducing Mercury's present-day mass and core-to-silicate ratio.

- This grazing impact scenario is statistically more plausible than previous catastrophic models, occurring in an estimated 20% of simulated systems, and accounts for "missing debris" by ejecting material with sufficient velocity to escape and be scattered by other planetary bodies.

- While primarily focused on collision physics, the proposed model is compatible with existing theories that explain Mercury's observed surface volatiles, such as subsequent delivery by comets or planetesimals, or slow accretion of interplanetary dust.

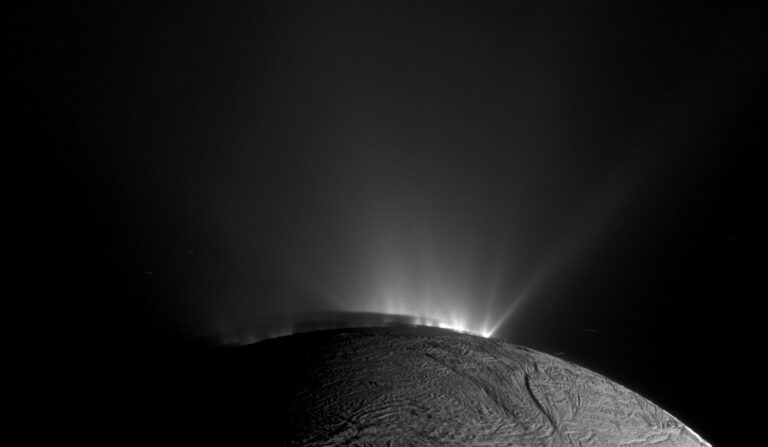

The early years of our solar system were a period of unimaginable chaos and violence, a gravitational free-for-all where colliding planetary embryos competed for survival. In this tumultuous environment, countless collisions shaped the worlds we know today, but one has remained an enduring cosmic mystery: Mercury. A new study suggests Mercury may have formed from a near-collision of two similarly sized bodies — a common occurrence in the solar system’s early years.

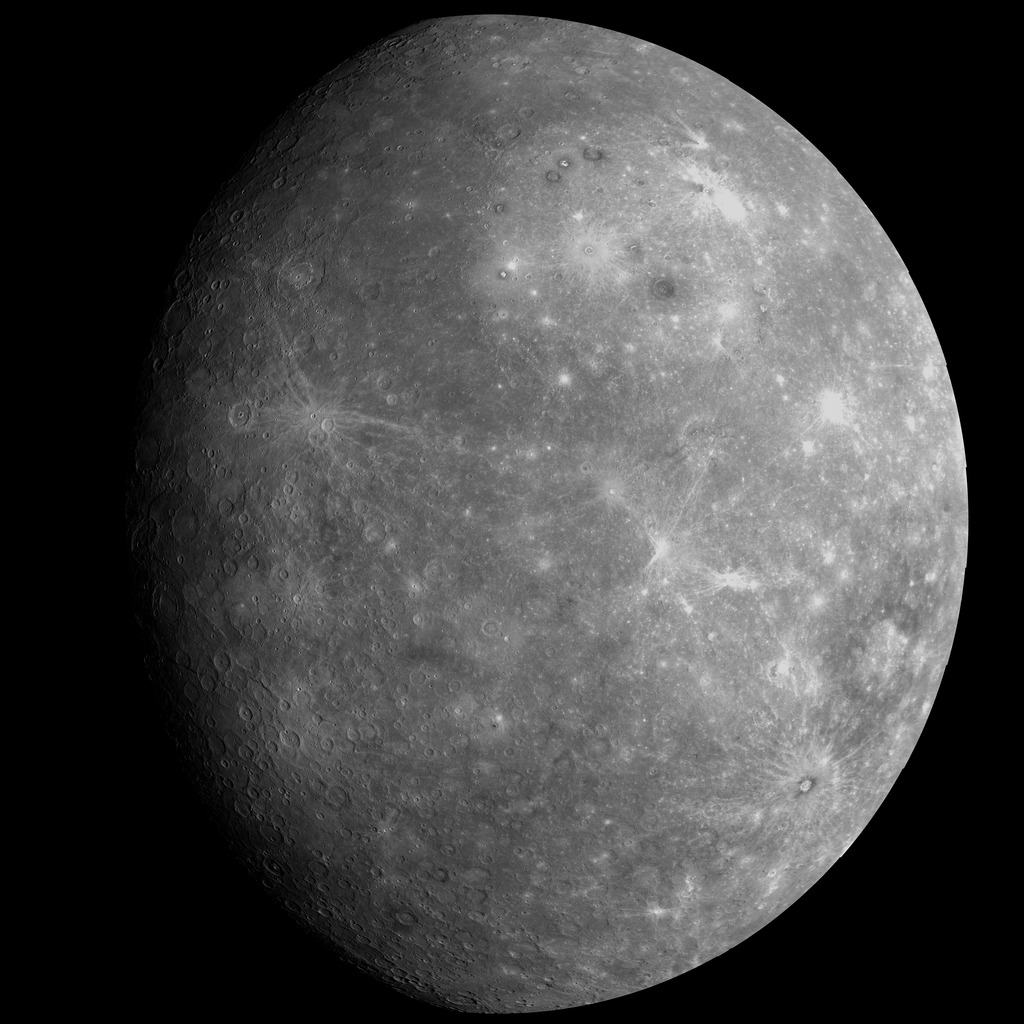

Mercury’s unique composition

Among the four rocky planets in our solar system — Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars — Mercury stands out for its strange composition. The planet’s core accounts for roughly 70 percent of its mass and 85 percent of its radius. Earth’s core, in comparison, comprises about 55 percent of its radius — a ratio much more common among our other terrestrial neighbors.

A grazing ‘hit-and-run’ impact

The origins of Mercury’s unique composition remain a mystery for scientists. The longstanding theory is that late in our solar system’s formation, the planet was impacted by a much larger celestial object, causing it to lose a significant portion of its mantle and crust. However, new evidence suggests it may have been shaped by a less violent grazing of two bodies similar in size.

“Through simulation, we show that the formation of Mercury doesn’t require exceptional collisions. A grazing impact between two protoplanets of similar masses can explain its composition,” explained Patrick Franco, lead author of a new study exploring Mercury’s origins published in Nature Astronomy and postdoctoral researcher at the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris in France, in a Sept. 22 press release.

The ‘Mercury problem’

The so-called “Mercury problem” refers to the difficulty of explaining two of the planet’s key features simultaneously. While Mercury’s large iron core suggests a history of extreme violence, such as a major impact that stripped away its outer layers, data from the MESSENGER mission also revealed that its surface is not depleted of volatile elements. This presents a challenge, as a catastrophic impact would have likely vaporized and stripped away these elements, along with the mantle.

This new study does not directly address the volatile problem, as its primary focus is on the physics of the collision itself. However, the researchers note that their model is compatible with several other existing theories that could account for the presence of these key elements. Even if a giant impact removed most of Mercury’s original volatile content, the planet could have experienced subsequent, non-erosive impacts from comets or leftover planetesimals that delivered new volatile material to its surface. Alternatively, the planet could have slowly accreted interplanetary dust over vast timescales, which would also have replenished these key elements.

Simulating collision scenarios

The idea that Mercury could have formed from a giant impact has been a prominent theory for decades, but the specifics have been difficult to prove. Earlier studies focused on head-on collisions involving bodies of very different masses, a scenario which proved to be extremely rare in planetary formation models. This led astronomers to propose a “hit-and-run” theory, where a proto-Mercury was involved in a grazing collision. The study from Franco and his team aims to test this specific “hit-and-run” scenario by using simulations to show that a more common, low-velocity, grazing impact between two similar-sized bodies could have created the Mercury we see today.

Franco and his team employed a sophisticated computational method called “smoothed particle hydrodynamics” (SPH) to investigate Mercury’s early life. This modeling technique is used to simulate how gases, liquids, and solid materials behave in motion, especially in deformations, collisions, and fragmentations. The SPH models allowed them to simulate the high-energy, deforming chaos of a planetary impact.

Through detailed SPH simulations, the team recreated the theoretical collision of two planetary embryos of similar size. They assumed a proto-Mercury with a composition similar to Earth’s and a mass of roughly 0.13 M⊕ (meaning 0.13 times the mass of Earth), which is more than twice the size of Mercury today. By adjusting the impact angle and velocity, the researchers could test how a grazing impact would affect the body. The goal was to find a scenario that would produce a final remnant with a mass and core-to-silicate ratio (the ratio of a planet’s dense, metallic core to its outer rocky shell) that matched Mercury’s present-day values.

The results of the study were compelling. The simulations showed that a grazing collision with a similarly sized body could strip away up to 60 percent of Mercury’s original mantle. This process would leave behind a core-dominant planet with a mass and iron-mass fraction that matched Mercury’s with less than a 5 percent margin of error.

The researchers were able to reproduce these results using parameters that are far more common in planetary formation models. While this new type of grazing impact is significantly more frequent than the massive, head-on events proposed in older theories — occurring in approximately 20 percent of simulated systems — giant impacts are still considered rare, making up only about 1-2 percent of all collisions in the early solar system. This makes the grazing impact a statistically much more plausible explanation for Mercury’s unusual composition.

A case of missing debris

The new model also solves another long-standing problem: What happened to the debris from the impact? In the old, catastrophic-impact theory, the debris from the collision was assumed to be re-accreted by Mercury itself. This would have made it impossible, however, for the planet to retain its unusual core-to-mantle ratio. In the new scenario, the grazing angle of the impact allows for some of the stripped material to be ejected with enough force to escape Mercury’s gravitational pull permanently.

But where did the other debris go? Researchers believe it was scattered away from the proto-Mercury by the gravitational pull of other developing planets, like proto-Venus and proto-Earth. This, combined with a weak drag force from the remaining dust and gas in the early solar system’s disk, could have kept the material from reaccreting onto Mercury. One exciting possibility is that this ejected rock was later incorporated into the formation of another nearby planet, perhaps even Venus.This new theory not only provides a compelling explanation for Mercury’s unique composition and the presence of volatiles, but it also helps us understand the wider processes of planet formation in our solar system. By studying these ancient collisions, we gain insight into how a chaotic “nursery of planetary embryos” eventually settled into the stable and well-defined orbital configurations we see today. With new missions like BepiColombo currently studying Mercury up close, scientists are awaiting data and samples that could help confirm this new theory.