Key Takeaways:

- A 3.5-gallon volume of deep space, specifically within the Milky Way's Orion-Cygnus Arm, would contain approximately 4 million neutrinos and about 13,000 gas atoms, predominantly hydrogen and helium.

- This specified volume could also infrequently include a dust particle, given its low average density of 0.0000001 per cubic meter.

- Numerous photons, emitted from stellar and galactic sources, continuously traverse this volume of deep space.

- According to quantum physics, the vacuum of space is not truly empty but is dynamically populated by virtual particles that instantaneously emerge and annihilate, consistent with the Heisenberg uncertainty principle.

What would a bucket full of deep space contain?

Richard Livitski

Seal Beach, California

One would think that this excellent question would be easy to answer: A bucket full of “deep space” would contain essentially nothing — and, well, there you are! Outer space is, after all, the closest approximation we have to a vacuum.

However, the universe is far more complex. So, let’s venture deep into the Orion-Cygnus Arm of the Milky Way Galaxy (where our Sun resides) with an average-sized 3.5-gallon (13.2 liters or 0.013 cubic meter) bucket. We’ll scoop up some “deep space” and see what it holds.

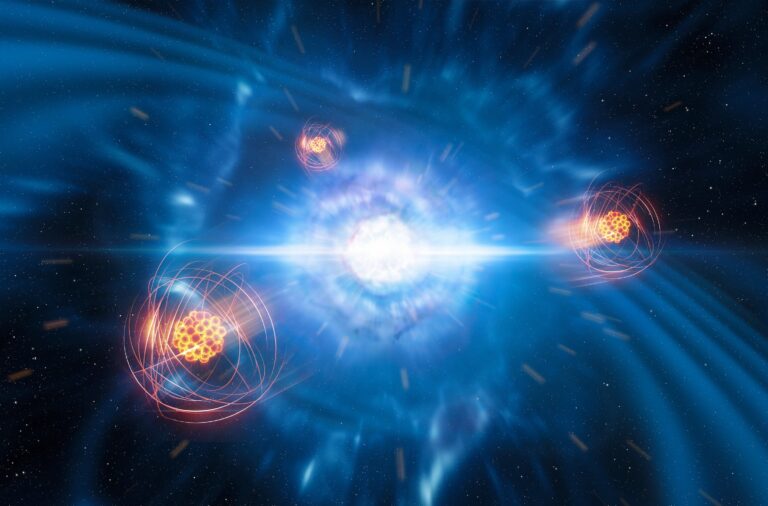

First, we’ll find about 4 million neutrinos. These nearly massless elementary particles travel close to the speed of light and originate from stellar cores, exploding stars, and other regions where nuclear reactions occur. Some were even produced just after the Big Bang. Neutrinos so pervade the universe that billions of them will pass harmlessly through your body in the time required to read this sentence. If we could see this neutrino profusion as little dots of light, it would blindingly illuminate our bucket.

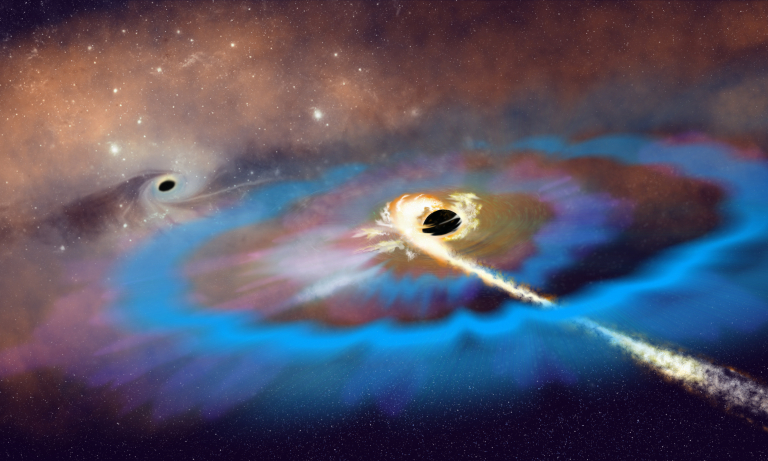

We will also find about 13,000 gas atoms, primarily hydrogen and helium, the two principal constituents of the universe. To put this number into perspective, a bucket of Earth’s air at sea level would contain about 1,300,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 gas molecules. So, 13,000 atoms is a paltry amount in comparison. And this density varies considerably — we would find even fewer atoms in the space between the spiral arms of our galaxy or in the vast chasms of intergalactic space.

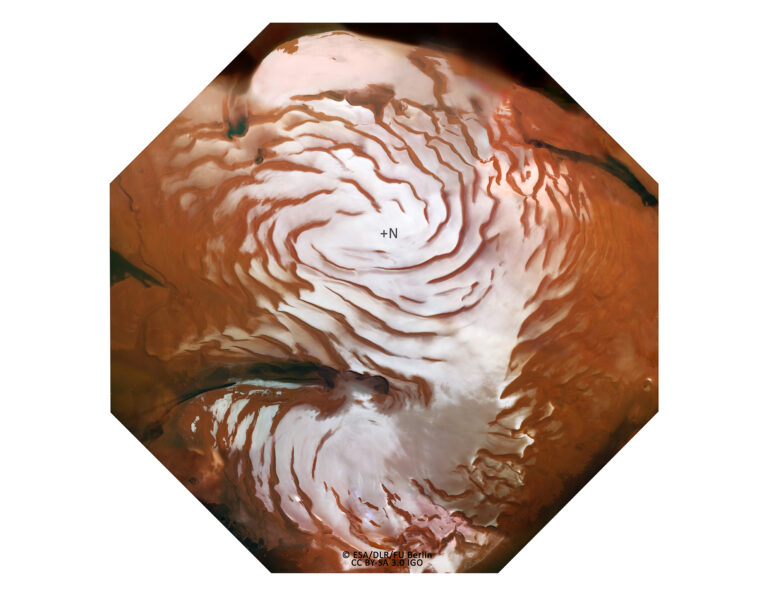

Also within our bucket might be a dust particle or two. However, the probability is low, considering that the density of dust particles in space is 0.0000001 per cubic meter. In other words, if we gathered 77 buckets’ worth of deep space, we would expect to find only one dust particle. Out here in the Orion-Cygnus Arm, if we were to collect all the dust particles within a volume the size of our planet, they would fill a space about the size of three sugar cubes.

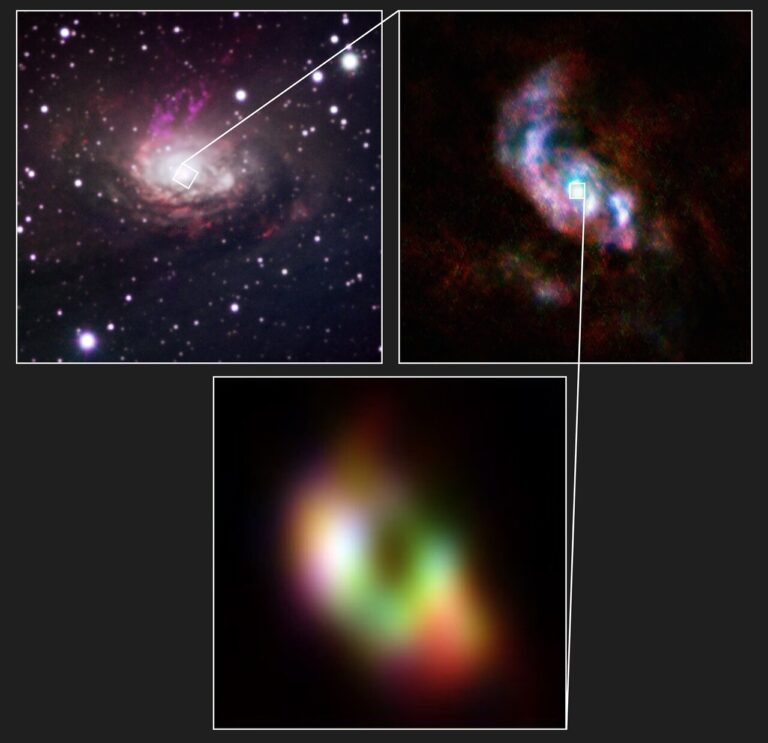

We will also find quite a few photons emitted from stars and distant galaxies, passing through en route to other regions. The only reason we can see stars is because photons travel from them to our eyes. Deep space is awash in these light packets darting about in all directions. If we could trap the photons like the neutrinos above, they’d be bustling about the interior of our bucket.

But what about deep space itself, apart from the neutrinos, gas, dust, and photons passing through? One would think that such a void would be, well, devoid of anything. Not necessarily. A strange concept from the thrillingly weird science of quantum physics is the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which states that one cannot precisely know both a particle’s position and its momentum. Additionally, one cannot precisely know the energy contained in a volume of space at every specific instant in time. Consequently, the vacuum of space is never empty, but is instead bristling with so-called virtual particles. These virtual particles, which appear in pairs, snap in and out of existence as they emerge and then instantaneously annihilate each other. They exist for such brief periods of time that they cannot be directly observed. No matter how closely we scrutinize our bucket, we won’t see them. But these, too, exist in our bucket of empty space.

So, a bucket full of deep space could contain an assortment of things, from neutrinos to dust to virtual particles. The density of our bucket’s contents would vary depending on our location, from our comparatively congested galactic spiral arm of the Milky Way to the remotest region of the Eridanus Supervoid. Just know that that bucket of empty space won’t ever truly be empty.

Edward Herrick-Gleason

Astronomy Educator, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador